Discover more from Notes from the Void

On May 24, 2020, the front page of the New York Times read, “U.S. Deaths Near 100,000, An Incalculable Loss.” The names of some of these deaths were printed below the headline, so numerous that they blended together into six gray columns of grief. A closer look at any spot on the columns revealed a stranger’s name and a few precious and inadequate words about their life, a portal into an entire world unknown and irreplaceable. “Romi Cohn, 91, New York City, saved 56 Jewish families from the Gestapo.” “Lorena Borjas, 59, New York City, transgender immigrant activist.” “Sandra Lee deBlecourt, 61, Maryland, loved taking care of people.” The entries go on and on, all 1,000 of them representing only one percent of the dead. These were the first Americans to die of Covid, and we were a nation in mourning.

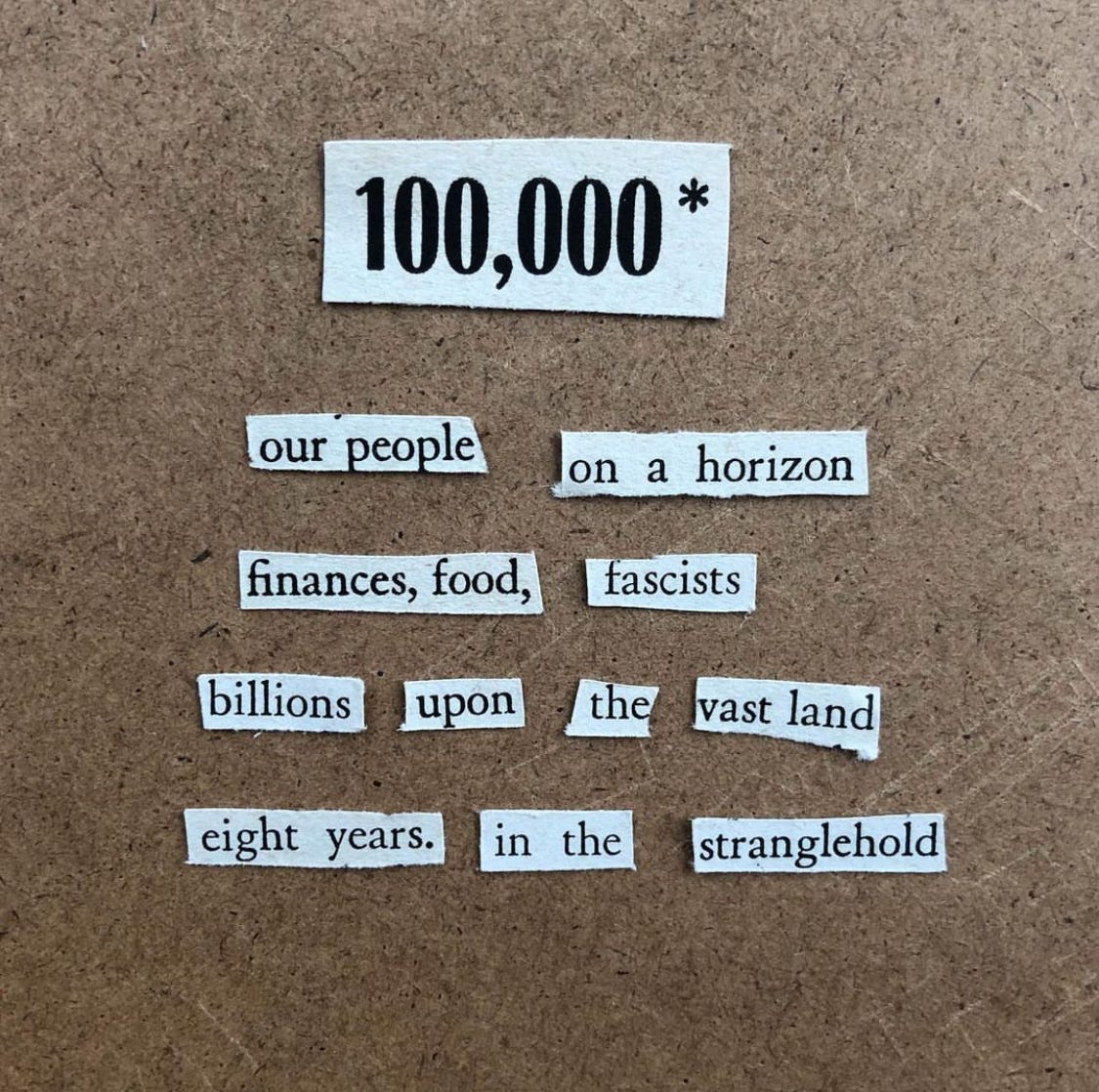

Around the same time, I began making cut-out poems with my partner while we passed the time at home. It was a way we could process some of the grief we had from the sudden arrival of this catastrophe. We didn’t have a lot of words in us those early days, so having them supplied by the magazines around the house was welcome respite from the impossibility of creativity in the midst of crisis. Arranging them was soothing and surprising, pandemic poems somehow emerging no matter what the source material, what order we arranged the fragments.

One poem in particular hit me hard. It was as if the pandemic were speaking directly to me:

The asterisk in the poem’s title has haunted me for four years, as if the poem knew more than I did about what I was in for, what we were all in for. How many more deaths lay behind that asterisk? What gulf had yet to open up and swallow us whole? We were billions upon the vast land, and we were waiting to learn our fate.

I have returned to the poem once or twice a year since its creation as if returning to an old prophecy to help guide me in the midst of this yawning future. The asterisk winks at me and reveals more: the interpretations change, something new and troubling makes itself known as time wears on. It has become a sort of ritual for me when I feel lost in this pandemic.

At first, I believed that the eight-year “stranglehold” would be two terms under the regime of the man in power at the time. But elections came and went, and the right hand passed the baton of imperialism to the left hand. I thought later that the eight-year stranglehold would be Covid itself, a horrifying prospect only one year into it. But I wasn’t ready for that possibility yet, so I tucked it away. I set my sights on the first line’s “horizon” that demanded attention and would hopefully reveal something important to me if only I looked hard enough, something about our collective future off in the distance, waiting to be grasped. But scrutiny yielded nothing but more questions, and our collective fate remained out of reach. I had to wait to know what it all meant.

As I waited, deaths accumulated. Four months after the New York Times article, the 100,000 doubled; in May of 2022 we hit one million recorded deaths in the United States. An incalculable loss. But this grim milestone, unlike its predecessor, was too late for mourning. By that time the director of the CDC had already announced some “really encouraging news”: three quarters of Covid deaths were in people who were “unwell to begin with.” As if they, too, didn’t want to live. The incalculable became horrifyingly calculable.

I was speaking recently with Johanna Hedva about their forthcoming book, How To Tell When We Will Die, and the topic of numbness and memory came up. As in the case of the Spanish flu, the Covid pandemic seems to have been erased; we are no longer moved by a death toll which far surpasses even the violent wars that have cloaked our country in death. Johanna brought up a point that Mimi Zhu makes in Be Not Afraid of Love: namely, that there’s a lot of life which requires temporary numbness just to get through the day. We simply cannot contemplate the horrors of humanity around the clock if we are to succeed in, say, making dinner. Some compartmentalization is required; some numbing greases the wheels of the quotidian. The problem, though, is when we manipulate that numbness to last longer than it should, when we let it creep across boundaries.

I think Johanna was right that numbness is one of the main coping strategies adopted during the pandemic. We live in a country rooted in the denial of our very basic foundations — namely, the transatlantic slave trade and the genocide of indigenous North Americans. It’s a country that adopted and expanded upon the notion of the “savage” and the “slave” precisely so we could become numb to our own atrocities, so our atrocities could be transfigured into destiny. We are, both politically and individually, committed to denial as a first line of defense against reckoning with our conditions. And though the pandemic’s initial eruption insisted on recognition for a short window, we returned to numbness at the first opportunity. This prolonged numbness is where our country finds itself today.

I don’t exempt myself from this critique. Part of what I feel I have lost is a kind of sensitivity to the incalculable loss — that part of the incalculable loss is indeed the atrophy of this very sensitivity in me, in all of us. I no longer shudder when I see the death toll, though it exceeds 14 million today. I no longer feel a pang of grief when I see that one thousand people in the United States died of Covid just this week. A calculated bureaucracy has taken up residence where something softer once lived in me. Though I didn’t choose this numbness (as I believe some others did), it has arrived just the same.

To be sure, I still dedicate an immense amount of time to preventing the death toll from climbing in my little corner of earth; to preventing myself from becoming part of this toll. I have worked tirelessly to try and build a world where we reject this death toll as just the cost of living our lives. But I can’t deny that a numbness is present in me, too — maybe not as much as others, maybe for not as long — but it is here nonetheless. This, too, is one of the incalculable losses.

Sometimes I ask myself whether I’m ashamed of this loss of sensitivity inside me, whether I miss the “me” who felt dizzy at the sight of 100,000 names. I am reminded, though, of what philosopher Lisa Tessman explores in her book Burdened Virtues: part of the harm of oppression is that it impedes us in becoming the kinds of people we want to be; it can create “conflicts between one’s dispositions and one’s own liberatory principles.” Indeed that is exactly what has happened to me — my empathetic disposition in the face of staggering numbers has waned, and I feel that this is in direct contradiction to my deeply held principle that each death should move us anew, that we should never become calloused to these numbers. I am living in this conflict.

Regret is an appropriate emotion to have in the face of this loss; it is a regret that I am not entirely the person I want to be, not entirely the person I ought to be. And yet, regret is not the only appropriate emotion; anger, too, has its place. The conditions that have engendered this callousness inside me are not of my own making. This is cause for righteous anger — anger at ableism, anger at the abandonment, anger at a world that allows the death toll to continue climbing. Anger is an emotion that says, “something valuable of mine has been taken.” And what could be more valuable to me than my own empathy, my own sensitivity to the preciousness of life? As Tessman writes, “anger, coupled with agent-regret, maintains a critical recognition of and oppositional stance toward the forces that inflicted one’s moral damage.”

Anger at this incalculable loss is also motivating. It is crucial that we avoid passivity in the face of the erosion of our sentiments; indeed I believe passivity in this moment transforms a case of complicated responsibility into a straightforward one. To not push back against how the pandemic is changing us for the worse is to allow our characters to reflect and reproduce oppression. For we have obligations even though we’ve been harmed; we have a duty to act on our liberatory principles even though the empathy which normally makes that choice easier has been damaged by the very conditions against which we fight. Our task is made harder by oppression, but this does not absolve us. Rather, we must act from within our own incalculable losses in order, maybe, to repair them; to prevent them in others; to become the sorts of people we want to be despite conditions that thwart us at every turn.