Memory Care

Tending to time during mass death

My 101 year-old grandmother, Letizia, is currently living in 1930’s fascist Italy under the reign of Benito Mussolini. She bikes to the outskirts of Florence most days to forage forgotten vegetables for her underfed siblings and huddles with them each night in bed to stay warm. She is Roman Catholic and so unthreatened by the recently adopted Manifesto della razza, which stripped Italian Jews of their citizenship as Nazism was emerging elsewhere in Europe. But she is desperate to escape her family and the deteriorating economic conditions in Florence, and she’s pregnant, so she absconds to Zurich to marry an American Jew.

We know she is in the midst of this because she mutters it under her breath in Italian, the only language she remembers, while living in the Memory Care unit of a geriatric care facility in Los Angeles, California. It is 2024 and nobody there speaks Italian except for her children who visit her when they can. Our favorite nurse speaks Haitian French which works for a while until Nonna forgets French, too. English is long-gone. Multiple waves of Covid have passed through her facility, and her own body, but somehow she endures each infection even as others in the facility do not. It is unclear what, exactly, is being cared for at Memory Care.

One of my own mother’s earliest childhood memories is of her sitting on her grandmother Ester’s sofa in 1960’s Brooklyn, her small legs sticking to the plastic sofa-covering that apparently all Jews of that era had. Ester was the mother of the American Jew whom Letizia married to escape Italy. The family photo album had been brought out, and Grandma Ester was narrating the turning of the pages, putting names to faces, and fates, one by one:

“Alter – killed by the Nazis.

[ ] – killed by the Nazis.

[ ] – killed by the Nazis.

[ ] – killed by the Nazis.”

They went through the entire photo album like this, a procession of the trauma that my mother was deemed old enough to learn was her inheritance. Neither my mother nor my grandfather Bill, Ester’s son, can remember the names of these murdered relatives beyond Alter’s. As Bill remarked before his death, upon realizing he had forgotten: “They’re lost in the mist.”

Not all of the relatives were killed by Nazis, as some lucky few escaped Poland before the borders closed. I myself owe my life to my second great-aunt Becky’s escape from Poland at the turn of the century, when she came through Ellis Island as so many other refugees of her era did. But she was in my family’s minority, and the vast majority of her siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles, parents and grandparents were killed in concentration camps. Whomever Becky could not send money to in time was murdered. No wonder there was rage in Ester’s voice as she flipped through the photo album, a sepia procession of loved ones whose fate was so different from hers only because her older sister Becky ran out of time and could not choose everyone. One by one, and then all at once, my family suffered the same fate as all of the other Jews across Europe, what Hannah Arendt described as “monstrosities no one believed possible at the beginning.”

Ester’s illustrated narration of death was at that point family tradition — each child, probably too young, was sat down and made to bear witness to the ways that the Nazi atrocities touched our own family. It was the living embodiment of “never forget,” shaping the self- and world-understandings of all of the Eisner children. It was how Ester cared for the memories of her murdered relatives: with rage and grief and an insistence on keeping the trauma alive.

Since my grandmother, Letizia, has forgotten large swaths of her life after Italy, I have been wanting to recover some of it, if only for it to live on in me. So I requested a few copies of her old journals as my mother and her siblings cleared out her house, newly uninhabited since the death of my grandfather. Other artifacts were distributed to me without hesitation — paintings, old photos, and some now-vintage glassware — but the journal request caused a lot of consternation. The siblings were split on whether to send them to me. I received mixed messages: that the journals were filled with religious musings that would completely uninterest me, but also that they were upsetting and would needlessly churn up the past. Many of the journals had already been thrown away because nobody could bear to read them. But a lot of energy was directed at making sure the remaining ones were not read by seemingly the only person who wanted to.

I never did get the journals — they, too, are now lost in the mist. But I didn’t insist on it, either. I knew if I insisted, I would get them. I also knew, though, that my mother and aunt were trying to protect me from the past by ensuring that they would be the last ones to remember it. I don’t know whether there is a grand secret that is being kept from me or whether I was just being shielded from a glimpse into the inner life of someone who was, all things considered, a difficult mother. All I know is that they felt I would be harmed by reading the journals, and that I’ve come to defer to my elders’ protective gestures even when I disagree with them. Sometimes forgetting is an act of care, too.

I am at the stage in life now when these directions of care are beginning to reverse — child on the precipice of caregiver, parents on the precipice of care recipient. My first real encounter with this was when my lifelong stepfather, Brian, was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s. He was brilliant and quick-witted and we watched as his vocabulary drained out of him, word by devastating word. Before all of his words were gone, he pointed at his head one evening and told me, “It’s chaos in here.” Words and concepts are intertwined, after all, so when one goes it drags the other down with it. In cognitive decline, the conceptual tapestry with which we make sense of the world becomes tattered; loose ends beget more loose ends. His eventually frayed to the point of dyspraxia, and then all we could do was love him until the end.

He, too, stayed in a memory care facility, but only for the last few weeks of his life. Memories are not exactly the main recipients of care at these places. Because people with dementia tend to “wander” and then get lost with no way of finding their way back, memory care facilities have more locked doors and secure perimeters than your typical hospital or household. The resident patients are kept inside, fed and bathed, and brought to sad “enriching” activities that nobody quite seems to enjoy. In this respect, the facilities succeed in caring for their resident patients. But part of me always gets stuck on the tendency to “wander” that we see in most people with dementia. Where exactly are they wandering to? I know I certainly wouldn’t feel at home in such a place; I would be lacking the very feeling of familiarity that I anticipate most craving during the last weeks of my life. Maybe they wander because they’re trying to remember.

It feels like a gift that he passed away eighteen months before the Covid pandemic began. It would have been devastation upon devastation to know that he had to be alone during his final weeks; that Covid may have swept through his care facility and killed its residents and staff; that we would not have been able to gather for his funeral. The memory of his death is mercifully uncorrupted by the callousness towards death that the pandemic heralded, especially toward those living lives deemed not worth living. Of course the pandemic was not the birth of this indifference; but it certainly shone a light on it, and I’m grateful that my memory of his death is not cast in that particular glow.

It’s not lost on me that Covid is now being shown to cause early-onset dementia, the very thing that killed my stepfather. Our collective refusal to reckon with the memory of the pandemic’s traumatic eruption is now causing at least some of us to lose the capacity to remember entirely, word by excruciating word — we are not caring for our memories and so we are being sent to memory care. I watch as my family members fail to adequately protect themselves from Covid, as if lining up for the same fate that they saw demolish the life force of our beloved Brian. What would it mean to genuinely honor his memory, not just the memory of his life but also of how brutally it was extinguished? I don’t know the answer; but surely it’s not this.

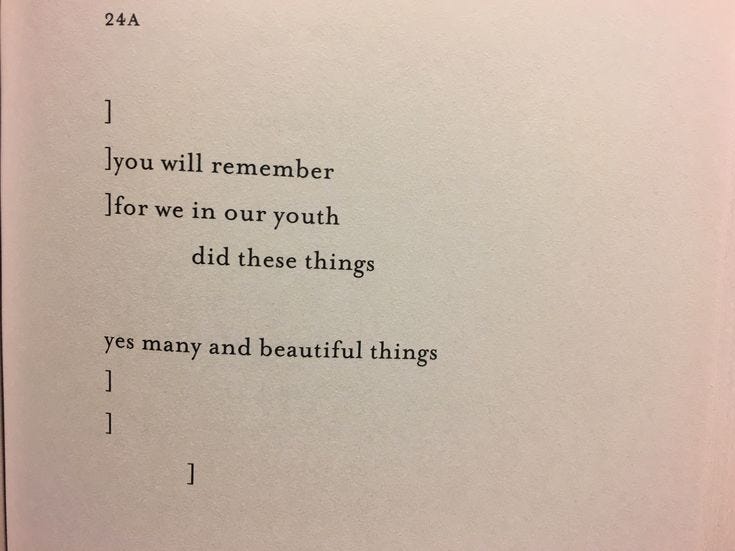

The most exquisite translation of Sappho’s poetry comes to us, I believe, in Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter, a majestic and tattered recreation of the ancient Greek poet’s hauntingly beautiful and modern poems from the sixth century B.C. As Carson explains of the source material: “Of the nine books of lyrics that Sappho is said to have composed, one poem has survived complete. All the rest are fragments.” Rather than patch over these temporal erosions as so many previous translators have done (with a creative license that exceeds the bounds of “translation”), Carson instead places them front and center, with brackets and gaps showing us how much has really been lost.

Page after page is filled with forgetting, sometimes so prolific that the entire surface is blank save for one impossibly preserved word: robe, swallow, barefoot. There’s an honesty in this translation that invites us to reckon with what we as a civilization have lost to history — within these empty brackets are wars and fires and faces long-since lost. Each bracket contains the tragedy of never again being able to read these poems in full. They invite us to grieve.

And yet, the beauty remains: the brackets and the words weave together to create what one commentator describes as “lace on the page.” Remembering and forgetting bound up in a delicate web — this, to me, is how we honor our memories. It is allowing time, the ghostwriter of all our stories, the credit she is due. Each of time’s erasures introduces another layer of devastation to the all-too-human longings already present in Sappho’s poems themselves. And if we’re honest, they remind us that we, too, are vulnerable to this same fate; we, too, will lose our words one by one.

I can’t help but think about the wholesale erasure that is happening in Palestine today — the erasure of entire families, neighborhoods, and archives, each one a universe unto itself. How could this be done in the name of Grandma Ester, whose dedication to remembering what happened to the Jews was seared into the minds of all her grandchildren? How could “never forget” for the Jews become “never remember” for the Palestinians? That this genocidal erasure is being funded by the United States, my own country of citizenship thanks to the refuge it provided for Jews fleeing Hitler, fills me with anguish. We are living in the midst of unspeakable evil, and yet we have to find the words for it if only to give these stories a fighting chance. Time will overshadow us all, but our grandchildren will remember, the land remembers, and a few precious words will make it through.

Refaat Alareer was a Palestinian poet and professor murdered by the Israeli army in December of 2023; his brother, nephew, sister, and three of her children were all killed in the same airstrike. I hope that some fragment of his poem is what endures:

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze —

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself —

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above,

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love.

If I must die

let it bring hope,

let it be a story.