Palette as Portal

Optimism of the Will

In a recent trip to New York, I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s John Singer Sargent exhibit in order to bask in the work of the greatest portrait artist of the twentieth century. I had only seen his paintings once before, in Chicago, which quickly converted me into a worshipper of his larger-than-life portraits of the wives of capitalists adorned in silks and pearls and chiffons, the materials rendered with brushstrokes so effusive and instinctive that portraits from the masters that came before him seemed stagnant in comparison.

At the Met, I was finally reunited with these paintings and many more — all showing a painterly grasp of human expression that clearly had no time for the hagiography for which Sargent was likely hired. The expressions he captured on faces were so real, so momentary and subtle, that it’s hard to believe they were the product of hundreds of hours of careful painting and not the momentary release of a shutter. Sargent found his art in the midst of painting for the oligarchs of the time, and he found a way to both aggrandize and humanize them all the same. The material contradictions of his day were transmuted into something ecstatic.

What really stood out to me, though, was a small painting near the end of the exhibition, a sort of footnote to the grand portraits that preceded it. It belonged to that genre of art within art, when paintings in the world find their way into paintings yet-to-be. In this case, Monet is seen painting en plein air with his future wife Alice Hoschedé at his side, adorned in her Victorian whites among the now-familiar forests and prairies of impressionism itself. Monet sits working on a painting — indeed the painting would become known as Meadow with Haystacks near Giverny — while Sargent’s gaze and the viewer’s merge into one, viewer becoming painter, painter becoming paint.

A painting within a painting is a special thing: the artist can take more liberties, can adopt a style not their own, can render someone else’s work without the stigma of mimicry. It is a way that the physicality of a canvas can enter into what is normally a portal, a surface for momentarily forgetting where one is. Think of Velasquez’s Las Meninas with its own backside, stretchers and all, painted into itself; or Siries Cerroti’s self-portrait containing a portrait and palette in hand. Zoffany’s Tribuna of the Uffizi takes this concept to the extreme, with Renaissance and Baroque paintings so numerous that they fall off of the wall and into the hands of the people inside, held at an angle and reminding us, yes, that these paintings are indeed more than just abstract images; they have a weight and size.

Paintings in paintings are a form of play, of paying one’s respects, and Sargent was having his turn. After all, he was painting not only his friend, Monet, but one of the founding members of Impressionism, a movement the perfection of which Monet nearly achieved, at least according to Sargent. Thus Monet’s painting depicted within Sargent’s painting is done in impressionist style, a faithful representation of the master’s style; but so, too, is the rest of the painting — that territory of the canvas ostensibly reserved for Sargent and his style. It is as if Sargent’s admiration of Monet transformed his own gaze (and hand) away from the grand manner of portraiture and into the world of impressionism itself, so great was Monet’s influence on him.

Of note, and most exhilarating for me, was how Sargent depicted Monet’s palette:

It is an ecstasy of brushstrokes, a small frenzy of color in Monet’s lap. Sargent doesn’t even bother painting the palette itself — just the paint leaping off its edges with an impossible energy. It is, to me, the very heart of the painting, and the only place where Sargent deviates from impressionism, even presaging the abstract expressionism that would only emerge decades after both his own and Monet’s death. What greater ode to a man and his movement than to render his palette electric with an energy ahead of its time.

After all, painting a palette within a painting is even more radical than painting a painting itself. It is a moment when a painter gets to paint paint itself, pure color; it’s an opportunity to eschew representation and dive into the emotion and rapture of paint’s pure potential. Sargent placed pure energy into Monet’s lap, gave it color, and told us everything we need to know: in Monet’s hands, all is possible.

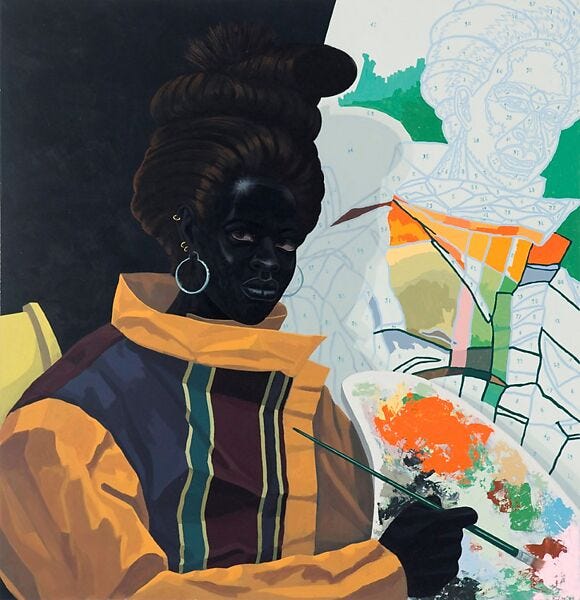

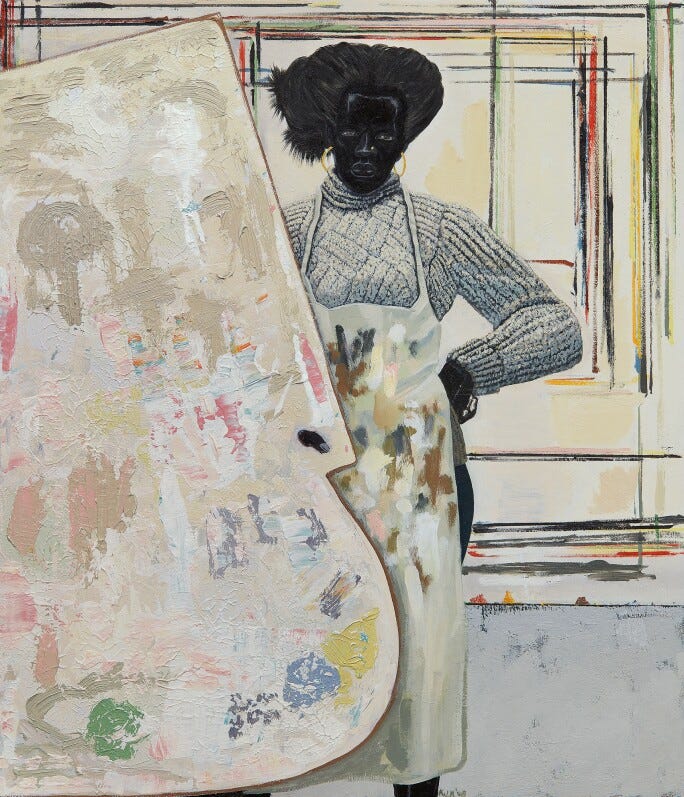

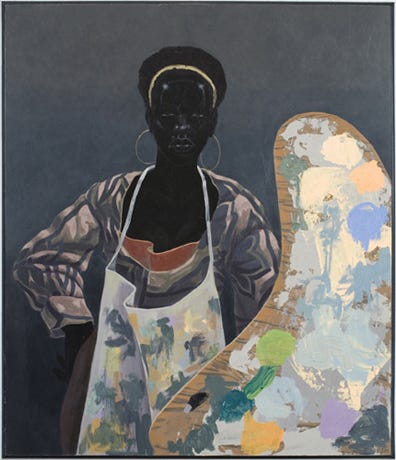

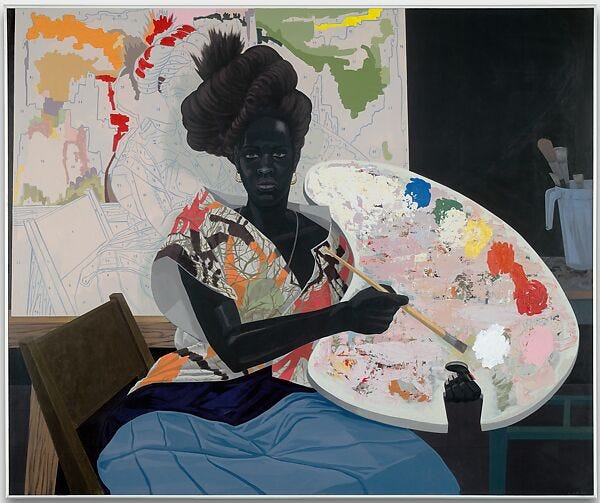

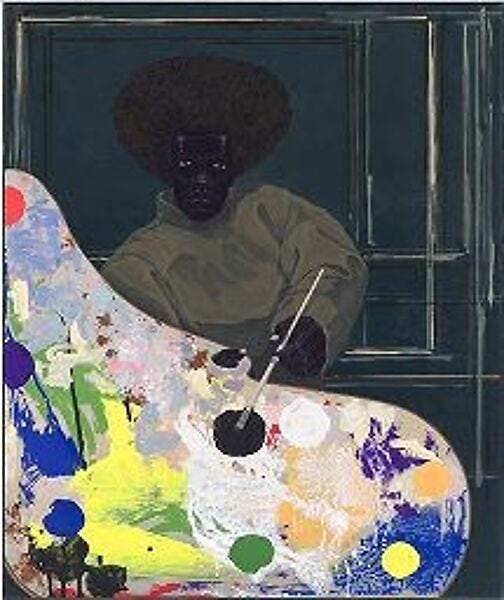

The palette is portal in the work of Kerry James Marshall, too, where Black figures hold their paint-covered palettes up to the viewer in gestures that are simultaneously offering and challenge. “Here,” these figures say; “you try.” Marshall’s exquisite 2016 retrospective at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art was appropriately titled Mastry, invoking both Marshall’s rightful place in a lineage of portraiture masters like Sargent as well as his challenge to the white antebellum masters who haunt Black American life to this day. Each palette he paints is evidence, source, symbol.

As a viewer of these paintings you are met with an uncompromising gaze, one whose hand holds the outstretched palette — always in the foreground for your scrutiny — as proof. Of what, though? Proof of competence, of mastery, of all of the skills that Black painters like Marshall surely were told were not within reach too often in their lives. The palette speaks for itself; again, all is possible.

Indeed the palettes alone would make for beautiful paintings; so, too, would all of the background paintings on which these figures are working. But together they are a symphony. Each painting contains numerous movements of art all in one: abstraction, realism, even paint-by-numbers. And each one exists both as undeniable proof of Marshall’s mastery but also as rejection of the traditional canon, insistence on painting in his way, with black on black on black. It’s no coincidence that some of these figures are dipping their brush into a blob of jet-black paint — they are choosing their subject, themselves, over and over again. The palette becomes a portal to a different world: one where Black life, Black subjects, Blackness itself, can take center stage.

I visited the Marshall exhibit before the possibility of a pandemic was made real in all of our lives, and the experience was quite different than the one I had at the Met just a few weeks ago. There was no lingering to be had at the Met, no prolonged meditations on the majesty of what paint can do in the right hands. Instead, the few of us who were masked scurried around all the other scurriers, phones out, packed into a sweltering summer museum. Kids were bored, parents were coughing, and each moment I spent in front of Sargent’s paintings was cast against the background surveillance to which those of us still taking Covid precautions have become exhaustingly accustomed. Is the coughing man sick, or does he just seem old? Is that woman wearing a mask because she’s sick, or trying not to get sick? There’s only so long one can be vigilant before one has to return to the fresh air outside, no matter how stunning the paintings on the walls.

And yet, I was out, which is more than many of my friends and comrades with Long Covid can say. I was upright, I was walking, I was in the light, I was listening to the sounds. So many people I know have lost so many of these abilities to the very virus from which surely some at the Met were suffering that day. So many would bargain away so much just to be able to walk up the Met’s front steps. My vigilance is a privilege, for it signals that I still have so much health to protect.

In all of this, I can only hope that the radical possibilities that I felt from witnessing a masterful painting of a palette — of witnessing a palette as portal — are brewing in the present moment despite the mass denial we see all around us. Antonio Gramsci (via Romain Rolland) famously described his revolutionary mindset in the midst of Italian fascism as “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” What better synthesis to carry us through the present day? It’s not enough that those of us with energy to spare simply hope for a better future without connecting that hope to our will; we have to be disciplined in our hope, refusing to do the work of fascism ourselves by mistaking our rightful pessimism for despair. This requires turning towards action and building the world we want to see right here inside the world we want to leave behind — a world where care is made central and our disabled comrades are no longer abandoned. Like the painted paintings in Tribuna of the Uffizi, each effort is both portal and presence, showing us all of the ways that our reality can, indeed must, be different; and each one shows us that our own hands are the best place to start.

For more on portals, see Julia Doubleday’s recent essay: